Editor's Choice

The Portuguese "India Run"

Erin Pearson

In 1497 Vasco da Gama commanded the First Portuguese India Armada from Lisbon to the west coast of India. Da Gama’s voyage built on Bartolomeu Dias’ expedition of 1487 during which Dias mapped the Cape of Good Hope. Da Gama’s voyage pushed on, rounded the Cape and travelled into the Indian Ocean; into waters that had never before been traversed by Europeans.

Da Gama’s successful journey to India opened up the spice trade and meant that Portuguese, and subsequently other European, traders could gain direct access to the spices and goods from India that for centuries had been traded via merchants from the area, via the Mediterranean. The reduction in cost for these popular spices revolutionised commerce and trade between India and Europe and situated Portugal at the centre of this trade.

The sailing routes mapped by early explorers such as Dias and da Gama were used by countless subsequent expeditions; centring these trade routes in Portuguese maritime history.

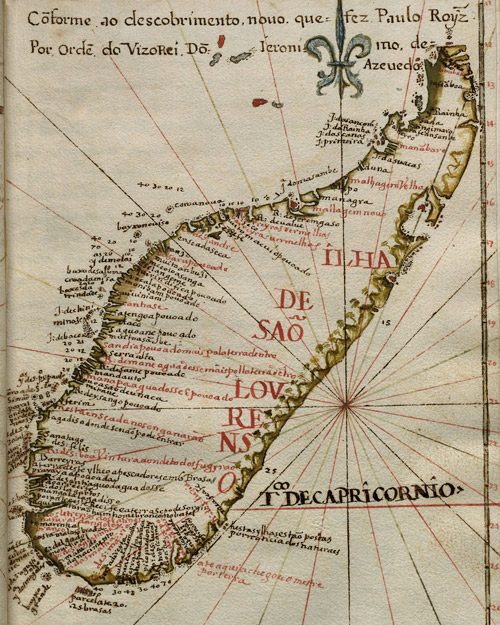

The Regimento de Pilotos e Roteiro da Índia Oriental contained with Age of Exploration is a Portuguese manuscript guide to be used by navigators sailing from Portugal to India. Written in 1631 it contains instruction, navigational aids, and sailing directions for a number of coastlines and courses across the Pacific.

The author, D. Antônio de Ataíde, wrote this work over 100 years after Vasco da Gama made his inaugural voyage from Lisbon to India in 1497.

This document is a key source that compiles together maps and information about these routes and the development of these routes over subsequent voyages after Vasco da Gama’s success. It allows readers access to a fascinating period of history during which European explorers began to search beyond their known boundaries into new frontiers.

Writing for Survival: The Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette

Amy Hubbard

“[W]e think we may be pardoned for a slight retrospect of our social and domestic economy since that Giant Ice said to us “Thus far shall thou go, and no farther” (The Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette, January 1853)

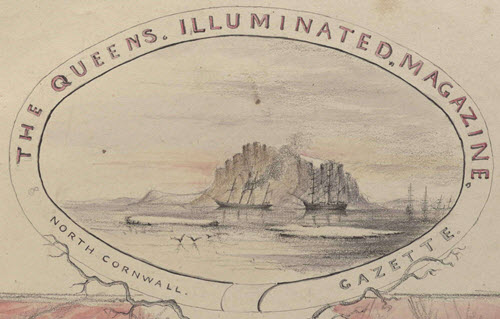

Throughout the age of exploration, the Arctic region’s equally treacherous and captivating environs continue to capture the imagination of explorers and the public alike, with such an extreme climate leading to incredible tales of survival, death and discovery. One of the most famous and tragic of Arctic voyages is Sir John Franklin’s failed search for the Northwest Passage in 1845 which itself was the impetus for over 40 search expeditions, each with its own remarkable story to tell. One such search expedition by the British Admiralty was led by Captain Edward Belcher in 1852. With five ships, including Belcher’s HMS Assistance and Sherard Osborn’s HMS Pioneer, the expedition was tasked with exploring various parts of the Arctic in the hope of finding traces of Franklin and his crew.

However, as was a common risk for ships in the Arctic’s icy seas, HMS Assistance and Pioneer became trapped in an ice pack at Northumberland Sound in the winter of 1852, and here they would remain until both ships were abandoned in the summer of 1854. It was during this long period of inertia that The Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette came to fruition. Hand-written and illustrated by the crews of HMS Assistance and Pioneer, this unique manuscript periodical offers an insight into the life (and imagination) of a crew trapped indefinitely in the Arctic’s solitary and uncompromising wilds, in search of entertainment, an alleviation from boredom, and a sense of normalcy.“Our small community in the Hull Ships Assistance and Pioneer already gives good promise of cheerfully combatting the rigors of an inclement climate and the corroding effects of monotony” (The Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette, October 1852)

Humorous, satirical and optimistically stoical in tone, the editions of the Gazette feature accounts of the expedition so far, reports on everyday life or fictional occurrences at the Northumberland Sound winter quarters, and a mix of carefully crafted tongue-in-cheek reader correspondence, reviews, notices and advertisements. Dramatic scenes are recalled in ‘The Arctic Expedition taking the pack off the Waigat, June 16th 1852’ as the writer romantically describes the “glorious excitement” of the “first conflict with our enemy the ice” whilst relaying the expedition’s dangerous navigation through the ice-strewn Waigat Channel. Equally dramatic, ‘A nip in Melville Bay, July 1852’ recounts the crews’ witnessing of the foundering of a whaler ship caught in the clutches of ice.

More fantastical, humorous and at times gruesome articles are found amongst correspondence pieces addressed “To the editor”. One crew member laments that polar bears “are not now what they used to be”, being presently too easy to kill, before going on to relay a gruesome tale of a bear attack during one of the Willem Barentsz expeditions. Another reader describes the details of an ‘Atrocious Murder’ in the heart of the crew’s small community, with the editor commending the swift actions of the local magistrate, “Admiral Walrus”, in confronting the situation. The victim is revealed to be an unfortunate Arctic fox named “Reynard”. Another letter speculates on the cause of the Aurora Borealis (a “band of magicians, philosophers or necromancers”) whilst others address popular concerns of the day such as how to define the “dandy” or how to accommodate Arctic delicacies into one’s diet. Perhaps most impressive is the account of the crews’ commitment to establishing “The Queen’s Arctic Theatre”, complete with playbills and performance reviews, and including an ambitious production of Hamlet.

These examples are just the “tip of the ice berg” of what The Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette has to offer. Read the full document here.

The Secret of the Unicorn

Matt Brand

The papers of Sir Joseph Banks offer fascinating insights into exploration, scientific developments and the intellectual life of his day. As well as accompanying Cook on his first voyage to the Pacific, Banks patronised a number of voyages of exploration and played a leading role in European academia. The range of individuals who corresponded with Banks is not only vast, but essentially a Who’s Who of the later years of the Enlightenment; his correspondents included the naturalist Peter Simon Pallas, the astronomer William Herschel, the polymath explorer Alexander von Humboldt, and even revolutionaries (in the form of Benjamin Franklin and Jean-Paul Marat.) Likewise, Banks’ papers have a global reach, sent from or describing territories in both the new and old worlds.

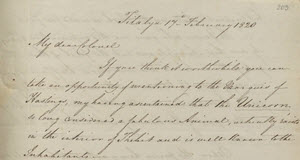

However, some Asian territories such as Tibet remained virtually inaccessible to westerners, even during Banks’ lifetime; and in February 1820, a Major Latter reported to a Lieutenant-Colonel Nichol that he was convinced that unicorns existed in this Asian land. A copy of this letter found its way into Banks’ papers, although it may not have reached Britain until after his passing (BL Add MS 33982, ff. 203-5.)

Latter noted that the ‘unicorn', so long considered a fantastic animal, actually exists in Thibit [sic] and is well known to the inhabitants’. This insight was gained from a man who had produced a manuscript which described such an animal, and witnessed them in real life; Tibetan unicorns were ‘fierce and extremely wild… seldom caught alive but frequently shot and the flesh is used for food.’ Herds of wandering unicorns could apparently be found ‘about a month[‘]s journey from Lhasa’.

Evidently aware that others might dismiss his letter (after all, he had opened it by mentioning that this news might be passed on to Lord Hastings, the Governor-General of India), Latter added that his encyclopaedia described the unicorn of antiquity as most likely an oryx, and that ‘this man knew nothing about our unicorn, but merely gave the description of an animal he himself… was well acquainted with’. Similar animals, he continued, were also described in the Bible, and had been observed in Californian rock art. Latter had approached the Sachia Lama, requesting that he sent ‘a perfect skin of the animal, with the head, horn and hoofs’, professing that ‘it will be a long time before I can get it down’.

Prior to the European reconnaissance, people with dogs’ heads or enormous feet which could be used as a parasol had been thought to inhabit parts of Africa and Asia. These ideas were dismissed as more came to be known of these continents; but even in 1820, so little was known of Tibet that Latter’s story seemed sufficiently credible for it to be passed on for the consideration of a respected naturalist.